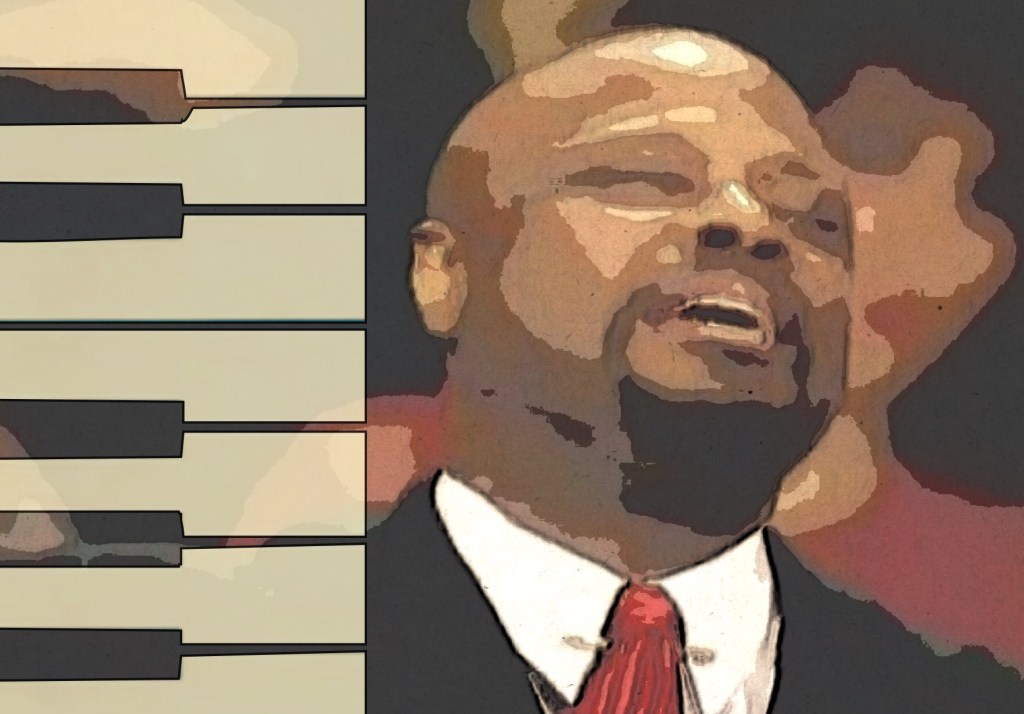

Five notes make a negro scale,

On a keyboard they are black.

Pitched to help the heart prevail;

Played to bring the spirit back.

They strike the chord of freedom,

And invite the voice to sing.

If you listen you can hear them:

Lilting, wafting, calling:

Calling to the lost, the grieving;

Beckoning the broken, the oppressed,

Singing something to believe in,

Bringing anthem to a quest.

. Sing to the notes of freedom; let them soar,

. Sing so we can hear them; forever more

© Tim Grace, 3 July 2011

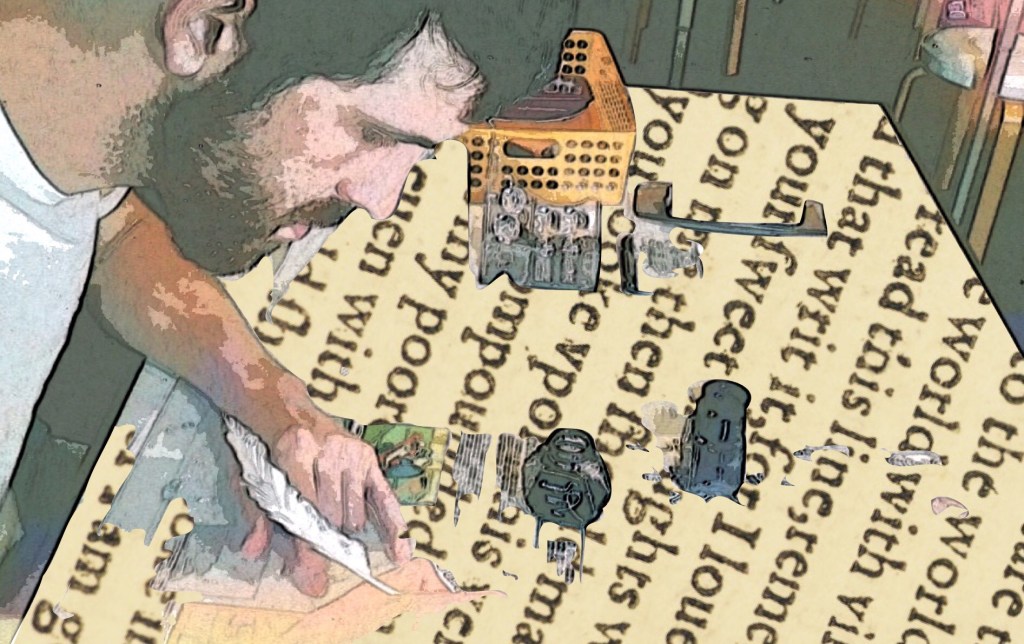

To the reader: With a surname such as mine ‘Amazing Grace’ has held a life-long interest. Occasionally, I’ll venture into an exploration of the song’s pedigree. The best of all explanations, in my opinion, is a 2012 sermon by Wintley Phipps. In this moving presentation Wintley explains the history of the Slave Scale and “shares how just about all negro spirituals are written on the black notes of the piano”. The writer of ‘Amazing Grace’ was John Newton (a slave trader) moved to give lyrical interpretation to his cargo’s plaintiff chorus.

To the poet: When you write in the footsteps of inspired art you take a risk. The comparison will more than likely reduce your words to mere exercise. And so, it’s best you respond accordingly… ensure the exercise is well executed; make it interesting.

five notes

five notes