Afterwards, when there’s nothing of him left

but a bag of bones in compounded clay,

he asks that we not mourn, or moan bereft,

as if scripted tight to a tragic play.

We are not to revisit memories

that through dredging would have our grief resumed.

We are not to resurrect miseries,

not to raise from earth all his bones exhumed.

Let his body go, let it rot in peace;

it wasn’t love got buried in this soil.

Love shall not perish, decay or decrease;

be content that all things but love will spoil.

. Love can not be buried six foot under;

. likewise, decomposed or split asunder.

© Tim Grace, 23 August 2011

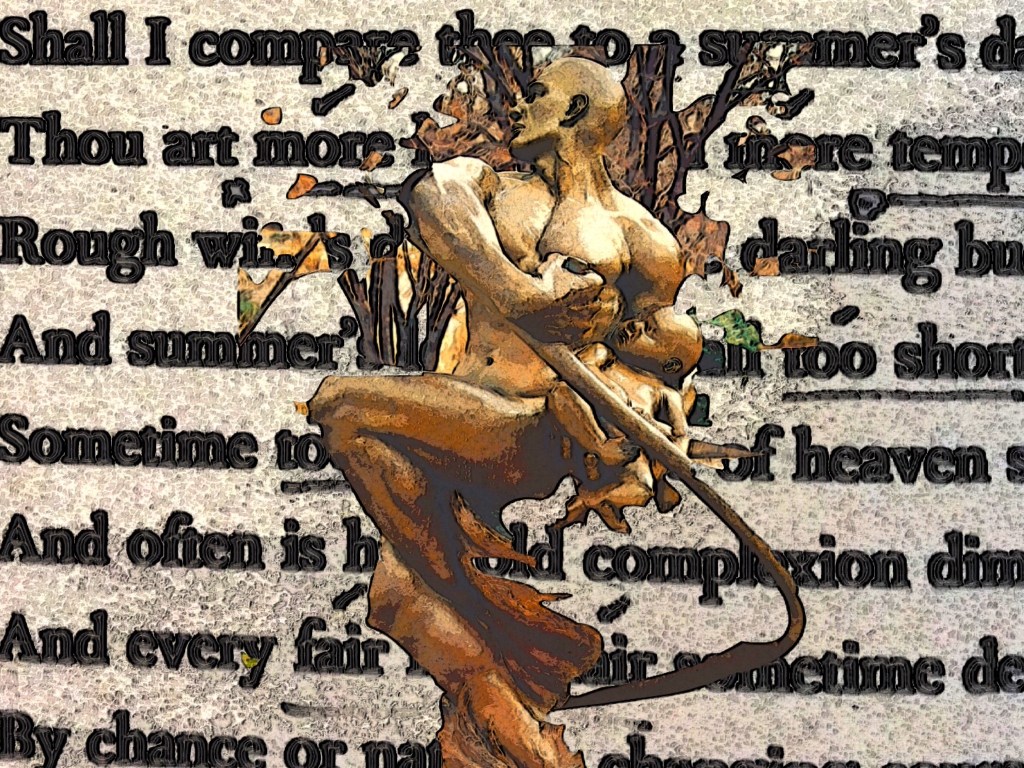

To the reader: Everlasting love; enduring love; love forever more. The possibility of remembrance beyond now. Appreciation as a welcome after thought that heartens the spirit of forgotten souls. Love, an essence so delicate in life, so enduring beyond the grave. In loving memory, we release the body of its burden and for eternity seek ever-lasting peace and resolution.

To the poet: There is a passage of Shakespeare’s sonnets (about 64 to 78) devoted to the potential of endless love. Afterwards – beyond images and artefacts; beyond graveyards and compounded clay ‘my spirit is thine, the better part of me’ (Sonnet 74). After words – ‘remember not the hand that writ it’ (Sonnet 71) for I am gone in all but spirit and soul. In his instructions to the living he implores release: let me go, let me pass… let me free.