Of all things perfect, none so more

than he who casts his eyes to mine.

In him, I see myself and so adore

the common make of our design.

All things from nothing yet compiled.

An angel formed of pluck and sprite.

He on me, has so been styled;

and so, gives rise to my delight.

I am touched that he would see me

as same; and to my loving eyes attach.

As if forever is but a certainty,

and never more our hearts unlatch.

. To what does this doting verse engender?

. ‘Tis a father’s love most mild and tender.

© Tim Grace, 24 July 2011

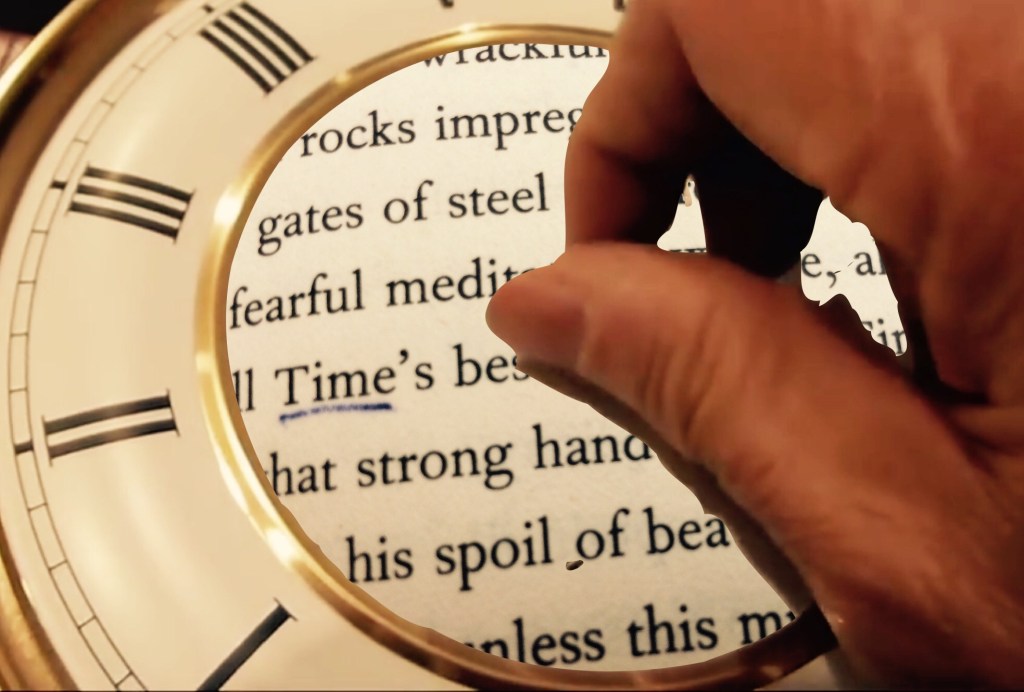

To the reader: As I do yearn for Spring, so I also long for the return of my youthful prime. I remember myself, not as the looking-glass portrays me now: aged with the deep furrows of time’s decay; etched upon my brow. No, my perception of ‘self’ lives in the recall of an untrammelled field; full of potential, far from the ravaging harvest of sickle and scythe; that leaves me exhausted in a decrepit state of waste.

To the poet: Dear Youth … love me tender… treat me with kindness and fair respect. In Shakespeare’s relatively short life he wrote of life with passion; an earthy, seasonal gift that so soon decomposes; loses its golden lustre. His season of fond recall was Spring, represented by the spirit of Youth and its zest for life. Life’s love found its perfect expression in the face of Youth… beauty’s image was His to bear: bounteous, brash, bold and abundant with promise.