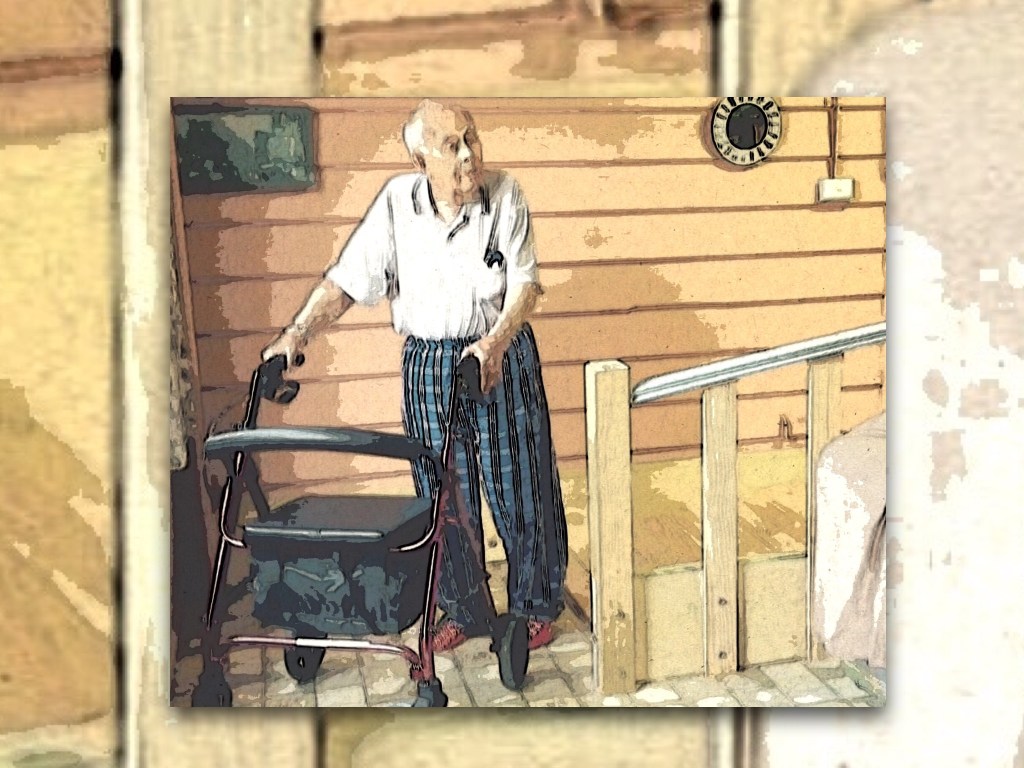

Once upon a time I presume he danced,

for there was rhythm in his shuffling gait.

I suppose there was a time when he chanced

to skip the pavement, to jump the fence, skate

upon thin ice; I presume this was so.

I suppose that once upon a time he

could run like the wind and swivel on snow.

May be once, this was how he used to be?

How he used to be, before age took hold

and shortened his strides into steps; weathered

then withered his reach; proceeded to fold

him into segments… with all parts severed.

. In this man there are vestiges of truth.

. Hidden in his shuffle is this man’s youth.

© Tim Grace, 1 April 2012

To the reader: The shuffle of elderly folk is rooted in the tentative first steps of childhood. Without momentum the ageing-frame hasn’t the balance to sustain a full-stride between steps; it’s lost the confidence to fall forward. In our prime the ability to walk is translated into the rhythm of life; through dance we skip; through sport we skate; as through time we scurry. Without stretch, and pace to match, we compensate … we walk with two feet not one, we shuffle.

To the poet: The strong structure of this sonnet descends into an awkward shuffle. It begins with stride and then falters. Beyond the first stanza, short-repeats struggle to complete a full line. Temporary anchors are scattered throughout. Stop-start phrases need backward attention. Through heavy compensation the sonnet’s rhythm is lost. In poetry, physical structure is as much a tool as any other literary technique; a poem is built as much as it is written.

steps into strides

steps into strides